Project Description

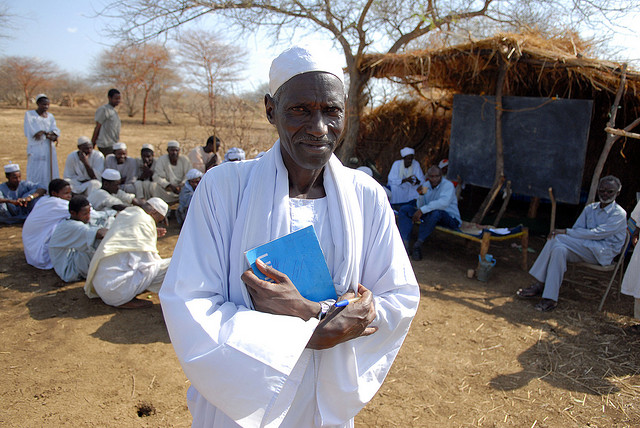

This January, the people of southern Sudan gave a resounding yes vote in their referendum on independence. The result leaves Northern Sudan facing a political and economic turning point as Sudan’s Comprehensive Peace Agreement (CPA) ends and Southern Sudan secedes. Much has been made of the risk of a possible resumption of war between the central government in Khartoum and the former rebels of Sudan’s People’s Liberation Movement/Army (SPLM/A), and many have questioned the viability of an independent South Sudan, a landlocked and desperately poor region in the heart of Africa. Yet one of the most important determinants of war and peace, both between and within the North and South, is how the Khartoum regime decides to deal with the momentous changes that Sudan is undergoing. If reformists in the regime — mainly young party faithful, pro-democracy Islamists and pragmatic business interests — are not provided with outside motivation, many of the same die-hard fundamentalists and security hawks that organized the brutal counterinsurgencies in the South and Darfur might again rise up. This would undoubtedly spur a new crackdown on opposition across Northern Sudan, possibly retightening the application of Sharia law and fueling new violence in South Sudan. The outbreak of renewed violence in the Nuba Mountains in June 2011 and Khartoum’s ruthless response are in part a consequence of insufficient creative engagement with the reformists, playing into the hands of hardliners.

This article examines two critical, interrelated factors shaping the internal deliberations and power struggles within the Khartoum regime: Northern Sudan’s economic future after secession and the role of the United States and the international community after the end of the CPA. President Omar Al-Bashir and Vice President Ali Osman Taha face internal contestation from both security hawks and reformists as they try to respond to the loss of 80 percent of Sudan’s proven oil reserves and associated petrodollars. The oil bonanza of the past decade gave the regime a second life and partially transformed Northern Sudan. However, despite serious investment in hydroelectric dams and roads, doubts remain as to whether Khartoum can withstand the gathering economic storm.

Read the rest of the article at Middle East Policy, Vol. 18, No.3